“Social partners working towards labour market revolution”, was the header run in Holland’s financial daily newspaper, Het Financieele Dagblad, on Saturday 9 January. In a nutshell, this revolution entails: a significantly shorter period of continued payment of wages during incapacity to work and creating a social safety net for freelancers. Yesterday, 3 February, saw the VAR regime (Declaration of Independent Contractor Status) put to rest by the Senate. Today (4 February) the SER is holding consultations on the future of the minimum youth pay scheme, a scheme that is essentially unknown in any other civilized country in the specific form adopted here, namely with enormous disparity between workers up to 23 years of age and those over. It is currently no secret that employers and employees, also those within the SER, are at their wit’s end over the Work and Security Act which, to put it mildly, is hardly turning out to be the success story that everyone had hoped for.

Perhaps it’s not such a bad idea therefore to take a renewed look at precisely what the fundamentals of good employment law are (including social security law and the relevant tax regulations based on those laws). 2016 may well turn out to be the year in which all stakeholders give serious consideration to what is required and then proceed to take the action necessary to regulate our labour market. Many of our labour market provisions are rusty, outdated or counter-productive, something that employers and employees alike are fully aware of. The question is whether recent strategies will be sufficient enough to create calm in the labour market over the next ten years. To this end let’s reflect on a number of recent events.

In terms of labour law 2015 was a turbulent year. Looking back, we saw for example heated discussions on the definition of “pseudo self-employed persons” (e.g. parcel deliverers for PostNL, orchestra substitutes etc.), on whether it should become compulsory for freelancers to take out a pension scheme, the FNV’s dissatisfaction with the wage agreement for civil servants, wrangling over tax credits, curtailment of payrolling in the brand new Redundancy Scheme, as well as a couple of new acts such as the Labour Market Fraud (Bogus Schemes) Act (already the subject of considerable criticism due to the virtually endless vicarious liability) and, the magnum opus of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment: the Work and Security Act, a legislative campaign intended, among others, to reduce the disparity between flexible and indefinite-term employment contracts, and which was denounced a failure even before its introduction (on 1 July 2015).

(To get an idea of the many discussions on this take a look at the Nieuwsuur programme broadcast on 10 December 2015: http://nos.nl/nieuwsuur/video/2074362-wet-werk-en-zekerheid-werkt-juist-averechts.html).

There was also the virulent report on contracting published by the FNV, which served to rock the fundaments of the collective bargaining negotiations. The front cover of the report leaves no room for doubt as to the FNV’s opinion on this new form of job creation:

The past year clearly saw the development of a central theme: the desired ratio between those formerly referred to as insiders, i.e. employees with a permanent contract, and the many others who do not fall under this category, namely the outsiders, albeit that my use of this term certainly cannot do everyone justice. The heterogeneous stakeholders in the debate may at times stand face-to-face or side-by-side. Simple fact of the matter is that whether we like it or not the group of outsiders continues to increase in size and significance, thereby creating a shift in the norm.

In the political capital, opinion is split on how to interpret this development. In the double edition of ‘Vrij Nederland’ (42/43 – 2015) Minister Asscher (Social Affairs and Employment) was quoted: “Why have we now started to accept what is not normal as normal?” According to the article his lamentation was referring to the fact that the indefinite-term employment contract (the “permanent contract”) was being pushed further and further aside in favour of an array of more flexible arrangements such as payrolling, contracting, and the increasing deployment of freelancers to do the work formerly performed by “proper” employees. Even though we have witnessed these developments over the past couple of years, you now see this reflected in the issues that have dominated the labour market/labour law discourse in 2015. Much has been written and debated recently on the underlying causes for this competitive stride. The labour market has been undeniably in a state of flux for a number of years. Some point the finger at the increasing internationalization that compels employers to keep labour costs low and where possible the labour force flexible. The competitive position on labour costs is in this context expected to primarily hit the bottom end of the labour market. Others point to the increasingly onerous provisions of the employment contract imposed through the complexity of legal and administrative obligations, the most frequently referred to of these being the obligation to continued payment of salary during incapacity to work, a subject that has been high on the policy agenda for some time. Employers simply no longer wish to give permanent contracts, because permanent has become too permanent, certainly when compared to the possibilities afforded by flexible employment. No doubt both groups are to some degree in the right.

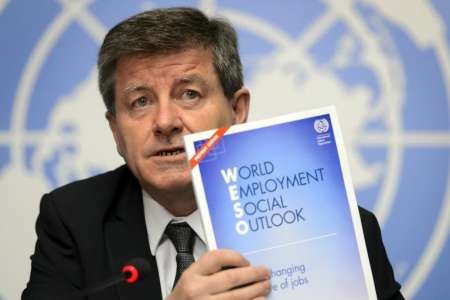

There are other, perhaps more perturbing explanations available. In an interview given by ILO Director General Guy Ryder in the Financieele Dagblad of 9 December 2015, he acknowledges that there has been a shift in the labour market, with the Netherlands at the forefront: “The ILO has 186 members and I can think of no other country with such a diverse labour market, so many temporary jobs, so many part-time jobs and freelancers.” In his opinion there is no turning back on the global flexibilization of labour. He refers to the development of disruptive technology, or what the French call the “uberisation of the labour market”: employment is increasingly structured through virtual platforms, instead of the traditional relationship between employer and employee: “It is becoming a purely commercial, transactional relationship.” He also discusses the shifting role of multinationals. His take on this: They employ fewer people but become parties responsible for organising the work. A job for one week, one day or one hour is no longer an employment relationship. The pace at which this changes varies from country to country, but everywhere I look I see the labour relationship being downgraded. Take for example the 800,000 zero-hour contracts in Great Britain. Five years ago this would have been inconceivable.” If Ryder is correct then flexibilization will continue to expand and contracting is heading for a golden future. Enough to make trade unions shudder.

Regardless of which is the more predominant of the explanations outlined above, the fact remains that the former relatively clear palette of labour relationships has become a complex mosaic of legal and economic disciplines, in which it is feasible for workers to simultaneously hold different roles, say for example in the case of a freelancer who also has an employment contract elsewhere. We can attempt to squeeze every worker into the mould. The Work and Security Act appears to have been designed partially with this in mind: reduce the disparity between flexible and permanent, and employer criticism of permanent employment and employee criticism of flexible employment will automatically dwindle, and certainly if at the same time pay-rolling and contracting lose a few sharp edges in the Dismissals Decree. This appears to have been the strategy of Minister Asscher. Putting aside the fact that the Work and Security Act will in all likelihood fall short of this goal, this strategy can only bear fruit if the changed labour market is indeed seen to be (almost entirely) a response to the disparities between flexible and permanent, in which the strongly-felt burden of a permanent employment contract colonises the anguish of employees (security, illness) and places this on the shoulders of the employer.

This review of past events facilitates a better-informed focus on the future. I feel that we have no option but to accept the multi-faceted labour market situation as a reality. The battle for the primacy of the permanent employment contract in its current form appears more and more to resemble a rear-guard action. This by no way means that we should relinquish the principle of a permanent employment contract. It means even less that we should allow all the other forms of employment relationship to develop ad hoc, or that we should assume that self-employed persons are able to fend for themselves and therefore just leave them to it (that same sentiment was asserted by many concerning workers in the 19th century). Everyone is aware that a lack of concise regulations and supervision will lead to a cowboy labour market, and for those in any doubt I recommend that you read-up on the turbulent history of temping agencies. However, in establishing appropriate regulations to govern employment relationships, the time has also come for acknowledging other regular variations alongside the established employment agreement or the freelancer. This will require an even closer evaluation of aspects such as the social position assumed by those employed, something already carried out in establishing whether a person has an employment contract or is a contractor, and something to which those who formerly presumed they were safely covered by the VAR will agree (it remains bizarre that the ministries of social affairs and finance were apparently unable to reach consensus on a definition for employment/employment contract). By way of glaring contrast: the statutory director of a large NV does not have to apply the protective regulations governing reintegration following illness and reassignment following dismissal which pertains to all employees; a low-skilled manual worker with a contract to perform services can expect to receive more than a basic social security benefit only if the “collective dismissal” was motivated in the interests of profit (he is not of course entitled to transitional compensation). It’s therefore not about the gap between flexible and permanent employment contracts but the gap between flexible and permanent work, bearing in mind the station in society held by the worker.

Surely a neo-liberal must recognise that a computer spilling out wage slips somewhere up in an attic room (a common practice with payrolling) cannot be deemed an employer. A staunch socialist executive must recognise that the labour market framework is lagging behind new developments such as Uber, not all of which by definition form a threat. We all recognise that a company director (or for that matter the author of this piece) is less vulnerable than a pseudo self-employed person working as a parcel deliverer or as a home helper. As far as I am aware The Hague has still not come up with a unison grand vision for the labour market as a whole. Piecemeal engineering has rubbed off some of the sharper edges of new developments, but the classic divide between employment contract and the rest is still seldom called into question. It is therefore interesting to see that the legislator now appears to be taking the first cautious steps in this direction by creating a social safety net for (some?) self-employed persons; we have already seen the introduction of a minimum wage for specific groups of self-employed persons.

It’s a start, but we need to go much further. How should we shape the debate in 2016 (and, I suspect, far beyond)? Personally I would be inclined to make serious work of configuring a new system of labour protection, composed of concentric circles. Certain aspects of the current labour law framework in broad have already demonstrated that this is indeed feasible: some self-employed workers are entitled, as previously stated, to the minimum wage, pseudo self-employed persons have access to collective protection of their interests (let’s finally also rid the 1927 collective bargaining law of the deadwood) , management board members cannot claim reinstatement of their employment contract, stock exchange executives are no longer classified as employees, the maximum daily wage establishes a clear income limit above which the solidarity stops (the transitional compensation route was evidently not practicable) and contractors fall under the same industrial injury provisions applicable to employees under Book 7 Section 658 of the Dutch Civil Code.

Naturally it would be presumptuous to here and now present a blueprint for such a Code du Travail, however, a group of experts with specialist knowledge of the schemes and the labour market could quite easily prepare an initial outline. It would not surprise me if the inner core – aimed to embrace all workers – comprised rules protecting against hazardous situations and against discrimination, and that further along a number of additional circles stipulated that employment terms and conditions can be established through collective bargaining, and the outer circle ultimately affords extra protection for specific groups of employees in situations involving severance pay, protection in the event of incapacity to work, and relocation. Regulation of the labour market can only succeed if every group gets its proper due.