The adage of the third Rutte government exudes positivity. The coalition agreement is therefore a child of its time: the financial crisis has been brought under control, populism has lost elections in Europe, consumer confidence is rising and unemployment is falling. This new reality calls for an appropriate package of proposed measures which, as usual, are a corollary of the game of giving and taking between, in this case, the four coalition partners. That game lasted 225 days, a record, and the coalition agreement covers 68 pages. I will discuss the second chapter: ‘Security and opportunities in a new economy’.

Proposed measures are anticipated in the area of employment and enterprise—Liber Dock’s focus area.

First employment: although the Work and Security Act, which was introduced in 2015, the magnum opus of the Ministry of Social Affairs and Employment (SZW), has made dismissal law fairer, it has certainly not made it simpler. Moreover, the difference between permanent and flexible work has hardly been narrowed down: the permanent contract simply remained too ‘fixed’ for this purpose, whereas the introduction of what is known as the system of grounds included Book 7 Section 669 of the Dutch Civil Code certainly contributed to it. From now on, an employer must fulfil at least one ground in order to realise a dismissal; buying off an incomplete file with a higher compensation, the order of the day under the system preceding the Work and Security Act, has become a thing of the past. The coalition agreement expresses the wish to make the indefinite term contract more attractive. For example, it offers employers more room with a new cumulation ground for dismissal – several half-full glasses now make one full glass – with the downside of this new indulgence being that the employer must pay up to a maximum of one and a half times the transition allowance. The court decides when there is reason for this increase, although I assume there will still be no room to take account of the consequences of the dismissal for the employee (which were abolished as a factor with the realisation of the Work and Security Act) or for taking into account serious culpability as this is included in any additional fair compensation. The provisions on succession of fixed-term employment contracts (the so-called ketenregeling) is also in the process of being redeveloped and will in part be restored to its former state in the pre-Work and Security Act era. These (and some other) changes are the result of the desire to soften the sharp edges of more than two years of the Work and Security Act. In a sense, this also includes the proposal to be able to start accruing the transition allowance from day one, whereby the waiting period of 24 months – which led to calculated behaviour by employers – will become a thing of the past. And so, the transition allowance becomes a real savings card.

The question is whether this will persuade previous employers to abandon all types of flexible arrangements, such as payrolling (which is hugely criticized in the coalition agreement). What may help in this respect is that the period of continued payment of wages in the event of sickness, greatly disparaged, will be reduced to a year for small employers. The ban on termination will remain in force for two years, but after one year the Employee Insurance Agency (UWV) will assume responsibility for rehabilitating the employee. Many experts question whether the UWV is equipped for this purpose and whether the new regulation will not be at least as expensive. More importantly, I believe that the impact of the change should not be exaggerated. Many employers will also experience the period of one year as the sword of Damocles, whereby screens with numbers showing how few employees are actually off work for a year or more, will make little impression. After all, as is often the case, it is all about image formation, and man is poor in his rational response to evil opportunities, so the Nobel Prize winner Kahneman teaches us.

As far as entrepreneurship is concerned, the coalition agreement has been worked out in less detail, but is no less ambitious. The government has not missed out on the plethora of self-employed people (zzp’ers); the proposed regulation in the coalition agreement making all those who earn less than a certain sum of money automatically employees and giving those who earn more than a specific hourly rate an ‘opt-out’ immediately caused great controversy. However, at the moment the plan is still too rough to comment on. The fact is, however, that if the lower end of the zzp market is compulsorily granted an employment contract, an important part of what is known as ‘platform work’ (provided by companies such as Uber and Deliveroo) will henceforth be performed on the basis of employment contracts. However, the trigger for many workers to become self-employed is the tax deduction that has often been called into question by experts. The government has stated that it has no desire to tackle this deduction (maximum of € 7280).

A second element worth mentioning is the exclusion of shareholders considered too activist. In order to protect ‘our table silver’, the government wants to regulate that when a listed company at the general meeting of shareholders is confronted with proposals for a fundamental change in strategy, the company can invoke a reflection period of up to 250 days, provided that this does not affect the movement of capital. During this period, account must be rendered to the shareholders for the policy pursued and all stakeholders involved in the company must be consulted (I assume this includes employee representation). This measure cannot be used in combination with anti-takeover measures taken by the companies themselves, such as the issue of preference shares or priority shares. In addition, listed companies with an annual turnover in excess of 750 million euros will be given the opportunity to request shareholders to register with the Netherlands Authority for the Financial Markets as major shareholder if they hold more than 1% of the share capital. The limit is now 3%. Smaller shareholders are therefore more likely to be targeted with the proposed measure.

The intended abolition of dividend tax has led to much discussion, particularly as the government has made little effort to conceal the fact that the decision was partly prompted by business opportunism: four large multinationals, including the former employer of the Prime Minister and the Minister of Finance, appear to have stated in a letter that their decision on whether or not to remain in the Netherlands also depends on the decision on whether or not to abolish the dividend tax. The fact that this measure should be seen in conjunction with plans to counteract letterbox structures, that withholding taxes on interest and royalties will be introduced on outbound financial flows to countries with very low taxes and that equity financing will become more attractive by limiting the deductibility of debt, has made little impression in the media to date. This in itself is not surprising – bad news sells better – but we must bear in mind that the abolition—and even more so in terms of numbers: primarily also benefits SMEs. These entrepreneurs-with-private companies will be able to pay dividends more often. Why: because it’s cheaper.

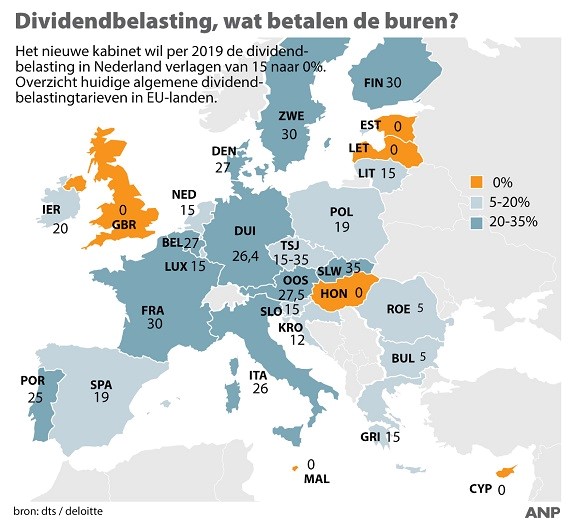

Dividend Tax, what do neighbouring countries pay?

The new government aims to reduce the dividend tax from 15% to 0% as from 2019.

An overview of currently applicable general dividend tax rates in EU countries.

Finally, the topic of pensions, which has its own paragraph (2.2). It contains no fewer than twelve proposals/intentions, which could cause some confusion as the introduction to the paragraph states that the SER is examining the possibility of a personal pension capital combined with the preservation of collective risk-sharing, and that the SER will shortly issue an advisory report on this subject that the government will study—at least, that is my assumption. I believe that this is one of the most fundamental pension issues in the coming years. However, anyone who reads further will notice that the proposals and intentions are very general in nature, such as’ Conditional pension accrual remains a responsibility of the social partners’ and the statement that the government ‘devotes attention to transparency and control of implementation costs’. It is almost impossible to disagree with that.

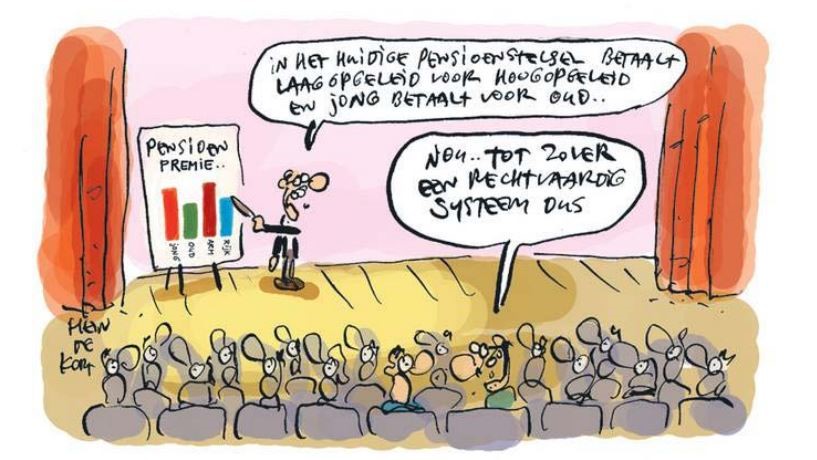

“In the current pension system the poorly qualified pay for the highly qualified and the young pay for the old…”

“Well… so far it sounds like a fair system”

The coalition agreement thus offers something for everyone. There is no ‘great story’, which with four different parties—two collectivist, two individualistic, two liberal, two conservative—is not surprising. The coalition agreement does, however, show that the parties have listened and that they recognise the bottlenecks in various areas that affect the daily lives of many people, and I believe that that’s a plus point. We’ll continue to closely follow legislative initiatives in the area of employment and enterprise with great interest.